At its essence, the soon-to-open 1904 World’s Fair exhibit at the Missouri History Museum is all about 120 years of stories and memories – some passed down through the generations, others revised to address the harsher realities behind the scenes of the once-in-a-lifetime spectacle that propelled St. Louis onto the global stage.

With a proclamation declaring, “Open ye gates. Swing wide, ye portals,” Louisiana Purchase Exposition Company president David Francis welcomed an opening crowd of 200,000 to the fair on April 30, 1904. By the time its run ended seven months later, the fair had attracted an estimated 20 million people.

Boasting “the latest achievements in technology, fine arts, manufacturing, science, civics, foreign policy and education,” the fair drew visitors from 43 of the then-45 states and 60 countries around the world. But the welcome was not all-encompassing.

For the millions of fairgoers who attended, they witnessed a grand pageantry stretching across 1,200 acres of Forest Park and Big Bend Boulevard, featuring hundreds of buildings and several grand “palaces.” But there were others at the fair whose presence contributes to a more complex history and continues to stir intense emotions to this day.

To tell a more complete story with the new, updated exhibit, the Missouri History Museum undertook the task of balancing the grandeur of the 1904 World’s Fair with the lesser-known narratives of blatant racism, including the exclusion of certain groups of people from attending the fair.

“For the first time, we are looking at these complexities in a way that we’ve never done before,” said Sharon Smith, curator of Civic and Personal Identity. “But rather than us trying to tell this story in its entirety, we have the voices of people from the community, people of Filipino descent, of Chinese-Americans and others that tell it in a way that makes sense –it’s just being honest and making sure everyone’s voices are included. This was an opportunity for us to get it right.”

The exhibit opens to the public April 27, almost 120 years to the day the city opened its doors to the world. It will feature more than 200 artifacts and hundreds of photographs, as well as original art and historical commentary from members of the St. Louis community, including Filipina-American artist Ria Unson, whose great-grandfather was brought to St. Louis from the Philippines to be at the fair.

Unson’s great-grandfather (“lolo” in tagalog), Ramon Ochoa, was among the more than 1,000 Filipinos transported to live on the fairgrounds’ Philippine Village exhibit in an attempt to showcase America’s imperial might, six years after its colonization of the Philippines in 1898. The display had Filipinos confined to a zoo-like habitat on full view to fairgoers, with different native tribes ranked on a scale between “civilized” and “savage.”

“As if the human zoos weren’t troubling enough, even more disturbing to me was the realization that some groups of Filipinos, including my great-grandfather, were essentially weaponized against our own people. Their role was to be living proof to the fairgoers how easily Filipinos could be molded into ‘model colonial subjects.’ They were also the perfect foil to the 40 tribes of indigenous people of the Philippines, who were presented as ‘savages,’” Unson said.

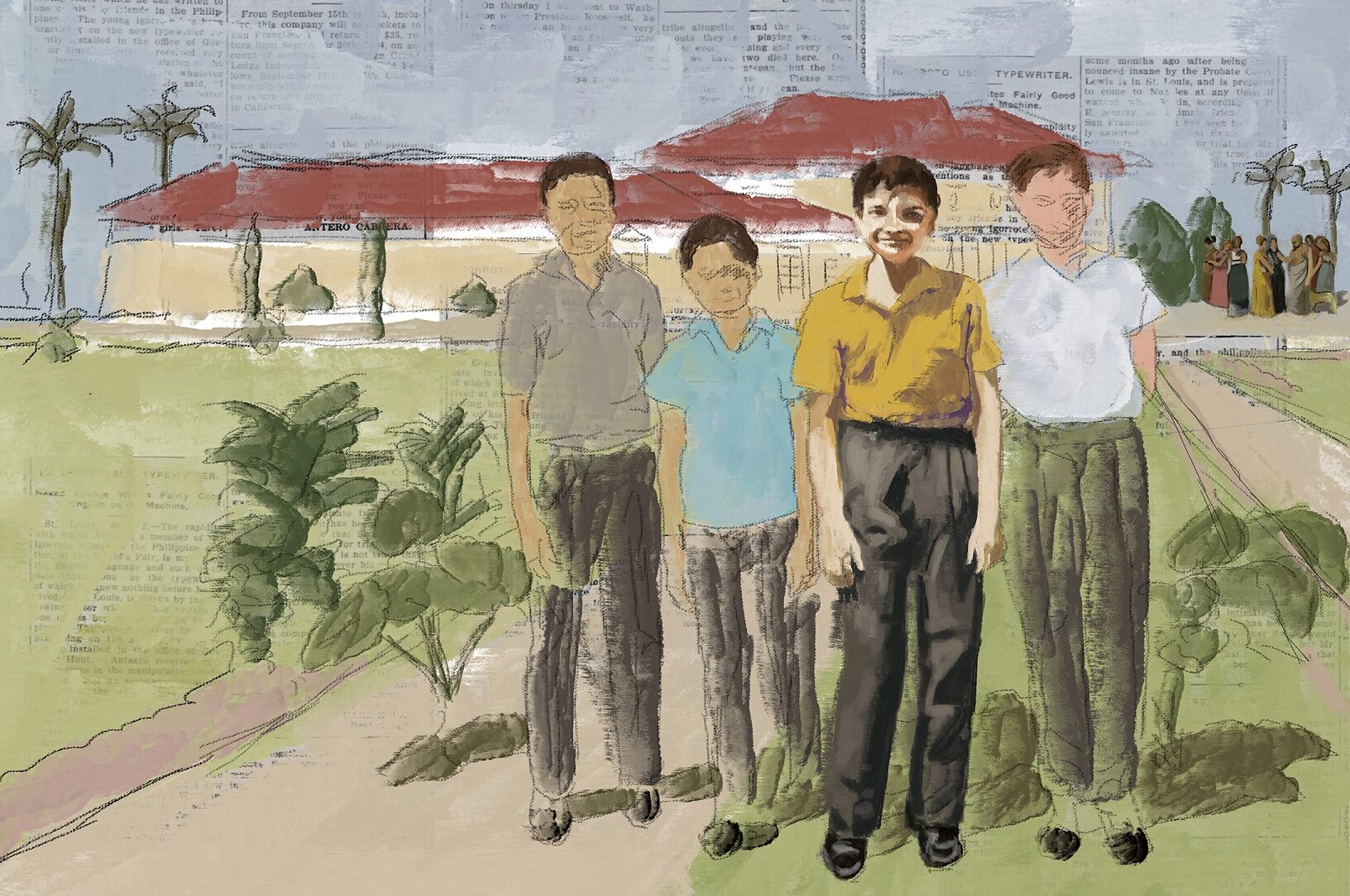

Unson’s artwork will be on display alongside the Philippine Village section of the exhibit. “Young Spartan” is a portrait of her uncle, Ramon, who is named after Ramon Ochoa.

“My uncle is the spitting image of my great-grandfather and I painted him at 16, the age that Lolo Ramon was in 1904,” Unson said. “Making art is my way of decolonizing, of interrogating my identity and my lived experience as a Filipino-American. It’s complicated, which is why the art itself has a multitude of meanings.”

Unson inserts her perspective in several ways, each layer revealing a truer account of the Filipino experience under American colonization and how its impact extends across generations.

“For example, for my inspiration image, I intentionally selected a snapshot of my uncle with his American expat friends in our neighborhood in Manila in the ‘50s, illustrating how Americanized we were generations later,” Unson explained. “I also painted this over newspaper clippings about the Filipinos at the World’s Fair. And finally, the title is a nod to an Edward Degas painting from the mid-1800s called ‘Young Spartans Exercising,’ representing the canon of Western, Eurocentric historical painting.”

Unson is among the newly discovered voices brought to light with the revamped version of the exhibit. Including this broader spectrum of perspectives meant reaching out to different communities across St. Louis.

“Once you make the decision to do that, you have to look to people that have that voice,” Smith said. “[The fair’s] history of discrimination against other groups had been long-forgotten or even avoided.”

Smith says in planning for the exhibit, the museum approached groups such as the National Association of Color Women’s Club.

“Just like other groups around the country, they had planned for their annual convention to take place in St. Louis in 1904, and they were going to have it on the fairgrounds,” Smith said, adding that when members of the group discovered they would likely not be served at the fair – and perhaps denied entrance – they decided to boycott it.

“The only people of African American descent at the fair were the workers,” Smith said, noting it wasn’t unusual to find persons of color relegated to low-status jobs servicing the masses at the fair.

Then there are the stories – even viewed with a more nuanced lens – that can attest to the endless fascination about the fair and its continued impact on St. Louis and beyond more than a century later.

“I happened to be in the museum doing a tour and was able to grant someone from out of town a peek at the exhibit,” Smith recalled, explaining the visitor, who was from the West Coast, grew up hearing about his grandmother at the World’s Fair. “His grandmother [who was Creole] was very light-skinned, but still would have been considered a person of color. She was able to walk on the fairgrounds several different times and bought all these souvenirs that she distributed among family.”

Smith took the visitor to see the exhibit’s centerpiece: a large-scale model of the 1904 fairgrounds created by a team of sculptors, designers, architects, artists and storytellers guided by historic photographs, maps and other archival documents.

“For him, he could see his grandmother walking through the fairgrounds,” she said. “It was a really powerful moment for him to see it come alive.”

Surrounding the model are four interactive stations, featuring tours “led” by diarists who documented the fair.

“You’re getting a tour from the perspective of somebody who was there,” Smith said, adding the tours explore a range of topics, including the food, art and architecture, and science and technology featured at the fair, as well as the Philippine Village, the African American experience and the fairgrounds today.

In addition, a few pieces will be on public display for the first time, such as the ornate desk presented as a gift to the president of the fair and later used in his office at Brookings Hall, and a large Japanese vase purchased by a visitor on site.

“It’s a very opulent piece,” Smith said. “A wealthy Central Missouri businessman who came to the fair saw this piece. Not only could he afford to buy it, but he was wealthy enough to have it shipped to his home in Springfield. It had been passed down from generation to generation.”

The exhibit is the Missouri History Museum’s biggest opening in 25 years, with a full weekend of celebration planned beginning Saturday, April 27. Highlights include live performances from local professional and high school bands, step teams and circus acts, a classic car show, an African dance workshop, a Japanese tea ceremony and more. Food trucks and food vendors, horse-drawn carriage rides and pedicab rides around Forest Park will be available for purchase outside the museum. Link to the Missouri History Museum’s page for more information on the exhibit and grand-opening festivities.