What does it mean to be an American? A Smithsonian traveling exhibit making its way to Soldiers Memorial Military Museum in downtown St. Louis this summer attempts to answer this deeply rooted question that continues to reverberate today.

The exhibition, “Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II,” chronicles the almost 80-year history and impact of Executive Order 9066, which authorized the internment of Japanese Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States entered the war, the nation was overcome by shock, anger and fear – a fear exaggerated by long-standing prejudice against Asians. In response, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which sent 75,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry and 45,000 Japanese nationals to incarceration centers, according to Soldiers Memorial managing director Mark Sundlov.

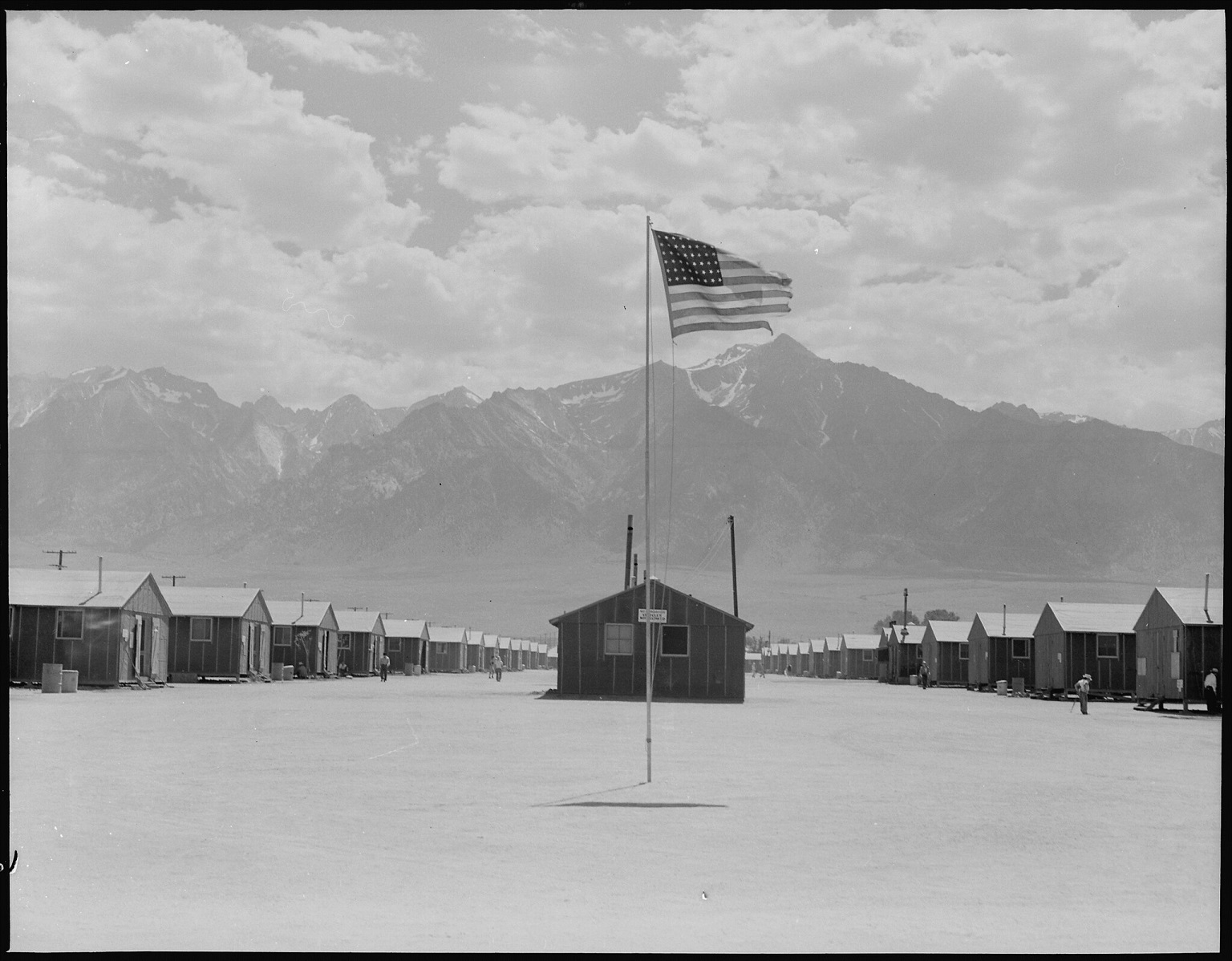

“The exhibition traces the story of this incarceration and the people who survived it,” he said, noting that families lived crowded together in hastily built camps, endured poor living conditions and were under the constant watch of military guards for two and a half years.

Meanwhile, more than 30,000 Japanese American men and women risked their lives serving in U.S. Armed Forces during World War II. Some of them were drafted, while others voluntarily left civilian life across the United States and the Hawaiian Islands to join the military. Still other service members had lived through incarceration themselves, Sundlov adds.

Heart-wrenching personal stories, fascinating documents, stunning photographs and engaging interactive displays come together in the exhibit, which embraces themes – such as immigration, prejudice, civil rights, heroism and what it means to be an American – that are as relevant today as they were 79 years ago, when the executive order was signed.

“Many of us are vaguely taught this history at some time in our lives, but few of us fully understand the tragedy of (it),” Sundlov noted. “The majority of the Japanese Americans who were incarcerated were second-generation immigrants (born in the United States) and had full, unquestionable United States citizenship. Due to a combination of war hysteria and racism, these U.S. citizens were stripped of their personal property and incarcerated in remote and isolated camps.”

More than 45 years after the executive order and following years of activism from the Japanese American community, the U.S. Congress formally recognized that the rights of Japanese Americans had been violated and President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. The law provided an apology and restitution to the living Japanese Americans who were incarcerated during World War II.

But for decades, the history has been heavily treated with euphemisms, according to Sundlov.

“Phrases like ‘evacuation,’ ‘internment’ and ‘relocation centers’ lessen the harsh, unjust and unconstitutional reality that Japanese Americans faced during World War II,” he said. “In reality, these U.S. citizens survived forced relocation and incarceration.”

Sundlov says the U.S. must perpetually confront its own hypocrisies and grievous actions if it is to continue to move toward a more just society for all of its citizens.

“The exhibit and its history should not be understood as a unique case study, but rather as a reminder that we must be constantly vigilant to protect all of our citizens equally and to be ever watchful for racist behavior and its insidious effects,” he said. “In this time of rising hate crimes against Asian Americans, this history is particularly relevant and comes as an urgent message that we must continue to strive toward our ideals, and we must support and protect all members of our communities.”

As part of the exhibit, local connections have been incorporated to tell the stories of Japanese Americans in St. Louis whose lives were forever changed by the incarceration camps.

“Although no incarceration camps for Japanese Americans were located in Missouri or Illinois during World War II, two of them stood about 450 miles away in Arkansas,” Sundlov said. “Many St. Louisans of Japanese descent have direct family connections to the more than 16,000 individuals who were incarcerated at the Rohwer War Relocation Center and the Jerome War Relocation Center between September 1942 and November 1945.”

Sundlov explains after the war ended and the camps closed, some Japanese families resettled in the St. Louis area. Japanese American students, workers and former inmates were welcomed to the region, where they found educational and economic opportunities, and were largely treated with kindness and dignity.

Some highlights include the stories of Japanese American students, including notable architects Richard Henmi and Gyo Obata, who attended Washington University in order to avoid internment in the camps. A variety of public programming featuring local connections will also coincide with “Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II” during its run from July 24 to Oct. 3, 2021.

Admission to the exhibit and to Soldiers Memorial Military Museum is free, but advance reservations are required. Visit mohistory.org/welcome-back for more information.

Mahalo for this well-written article.

Your readers may not realize that there was a larger population of nearly 160,000 citizens of Japanese descent living in Hawaii where fewer than 2,000 were incarcerated. Unlike the drastically harsh treatment faced by mainland Japanese Americans who were subject to intense fear and suspicion in their everyday lives that eventually led to internment, most of Hawaii’s multi-ethnic residents advocated for the fair treatment of its fellow citizens. Leaders such as FBI head in Hawaii Robert Shivers, YMCA leader Hung Wai Ching, University of Hawaii regent Charles Hemenway, Honolulu Police officer John A. Burns, Colonel Kendall Fielder, and military governor General Delos Emmons were among the countless government and community leaders in Hawaii who believed in and trusted their fellow citizens of Japanese descent that prevented mass incarceration from happening here. As a result, Hawaii provided most of the soldiers for the 100th/442nd units.

Also, the number of men who served in these units was about 10,000, not 30,000 as stated in the article.

Thank you for bringing the error to our attention. It has been revised.